Review for The 13th Doll – A Fan Game of The 7th Guest

It's been more than 25 years since The 7th Guest first debuted, and while its age is evident to modern eyes now, it's hard to overstate how big an impact it made at the time. Subsequent adventure staples like full motion video, pre-rendered 3D graphics and CD-ROM storage were little more than pipe dreams before Trilobyte's first-person horror puzzler made them standard; no less than Bill Gates proclaimed it "the new standard in interactive entertainment." Gaming would never be the same again.

The 7th Guest was so revolutionary that it’s easy to overlook just how enjoyable a game it was in its own right, and how effective it was as a piece of storytelling. All of its technical innovations were done in service of a macabre and surprisingly poignant tale about desperate people discovering the high cost of second chances, and the majority of its puzzles remain entertaining even today. It's a shame, then, that visitors to Old Man Stauf's mansion have had only one lackluster barely-a-sequel (The 11th Hour) to satisfy their desire for a return journey since the '90s. Original developer Rob Landeros twice attempted to crowdfund a third installment under the re-formed Trilobyte banner, but when those were unsuccessful it seemed likely that we'd crossed Stauf's threshold for the last time.

Enter indie studio Attic Door. Having worked for close to a decade on an unofficial sequel called The 13th Doll, they were unexpectedly contacted by Trilobyte in 2015 and offered a license to sell the game commercially if they could secure financing. They did, and now at long last this fan-made installment is complete and the mansion doors stand open once more. The end result is an admirable first effort by a novice studio that was clearly a labor of love for all involved, and despite some rough edges and a dependence on knowledge of the first game's events to be comprehensible (The 11th Hour, thankfully, goes mostly unmentioned), it serves as a largely enjoyable homage to a classic of the puzzle-adventure genre.

(Heavy spoilers for The 7th Guest follow, as it's almost impossible to describe this game without them.)

The 7th Guest ended with Tad Gorman, the child who'd been lured to Stauf's mansion to serve as a sacrifice, escaping the demonic toymaker's clutches and seemingly consigning him to damnation. The 13th Doll begins approximately ten years later with Tad a patient in a mental ward, where he relives his traumatic experiences in the haunted house and agonizes over the trapped souls of Stauf's previous victims whom he couldn't save. (This is the first of many convoluted story points: the opening narration states that Tad managed to free the souls of the other children, while the rest of the game says he didn't.)

Dr. Marcus Richmond, the asylum's idealistic new director, is advised by his departing predecessor to abandon any notion of curing the young man, as Tad appears beyond all help. Richmond, however, refuses to give up on a patient, and he suggests an unconventional method of exposure therapy: he and Tad will travel to the mansion together so that Tad can see there's nothing there to fear. This goes about as smoothly as you'd expect, as no sooner have they left the asylum grounds than Tad steals the doctor's car and sets out to finish what he started a decade earlier, leaving Richmond to follow behind in an effort to bring him back. (How Tad learned to drive when he's spent his entire adult life in an asylum isn't addressed.)

From here you're given a choice of whose story you want to continue, Tad's or Dr. Richmond's, and you'll follow your chosen character through to the end. As Tad you'll be guided by the mysterious Woman in White, a ghostly figure who tells you to free Stauf's victims by assembling the titular doll and performing a ritual in the tower above the attic. As Richmond it's Stauf himself directing you, insisting that the stories of his wickedness are vicious lies and promising you fame and success if only you'll help him complete "the Machine," which was to be his greatest work. Puzzles, objectives and story progression are entirely different across the two halves: some rooms are only available to Tad, while others open for Richmond alone, and as no puzzle repeats between characters you'll need two playthroughs to get the full experience. All told it took me about 20 hours to complete both parts of the game.

The 7th Guest was packed wall-to-wall with puzzles, and while most were pleasantly challenging there were a few (like the infamous microscope) that pushed up against the limits of fairness. For the most part The 13th Doll actually improves on this aspect, with a series of well-constructed challenges that equal the best of what the original had to offer while avoiding the worst. Several puzzles build off of ones that were present in The 7th Guest without ever feeling recycled or overly derivative. In a few cases a puzzle's objective was unclear and I needed the built-in hint system to tell me what my goal was, and I still don't quite buy the rationale behind the solution to one numerical puzzle, but most of the time your character will give you enough information to get you started.

As in the original game, your ethereal adversary (Stauf for Tad, the Woman in White for Richmond) taunts you as you play, but the charm quickly wears off as there's only a handful of lines for them to cycle through ad nauseam. A few even actively detract from the experience, like when I was repeatedly told in this 1930s period piece that I had "street smarts: Sesame Street smarts!" Still, the puzzles themselves are a joy, and on their own they make me excited to see what the developers do in the future.

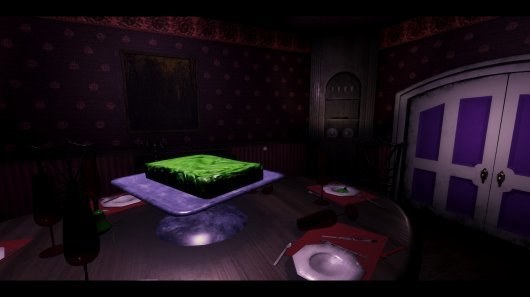

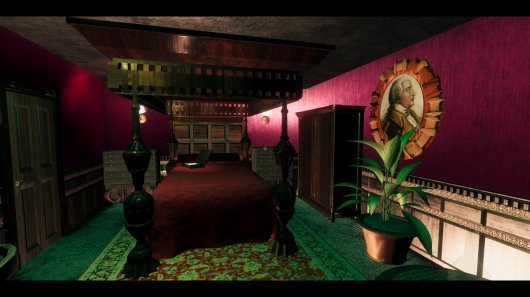

Gameplay is simple and much like The 7th Guest's, albeit with free range of motion in fully-rendered 3D rather than the original's pre-rendered semi-slideshow presentation. The manor loses some of its eerie atmosphere when you're able to move around it as you please—real-time lighting increases visibility but lessens the sense of dread—but it's been recreated quite faithfully. Spooky paintings and photos line the walls, seemingly innocuous pieces of scenery jump to unexpected life when you click them, and you never know when an otherworldly vision might materialize around the next corner. It's all visually well-realized, but I still found myself missing the feeling of creeping unease I sometimes got while playing The 7th Guest. As fun as it can be, The 13th Doll is never very scary.

Movement is via WASD with the mouse used for interactions, and the cursor is context-sensitive, changing according to what it hovers over: a beckoning skeleton hand for a door you can open, a pair of chattering teeth for an object you can manipulate, a drama mask to show that a short scene can be accessed, and a skull with a pulsing brain for when you've found a puzzle. (In a nice touch, these icons are exactly the same as in The 7th Guest.) Unlike last time you do have an inventory here, but it's only for storing hidden collectibles and the parts of whichever MacGuffin your character needs to assemble; you'll never need it to solve a puzzle.

As a fan sequel to a 26-year-old game, The 13th Doll understands that its primary audience is made up of people (like me) who look back fondly on the original, and those players ought to get a kick out of the many, many references and tips of the hat to The 7th Guest. These range from the subtle, such as a puzzle involving game pieces that resemble the original seven guests, to the overt, as when the in-game map names rooms after their previous occupants (the Knox Room, the Dutton Room, etc.). Callbacks to puzzle solutions from the previous game crop up in unexpected places without feeling forced, and gold coins depicting "memories" from before are scattered around the mansion for you to optionally find and collect.

All this means that The 13th Doll will be more difficult to appreciate if you've never been exposed to its predecessor or don't remember it well. While you can play the game from start to finish without knowing a thing about The 7th Guest, it doesn't go out of its way to catch you up. Tad's quest, for instance, hinges on freeing the stolen souls of the children Stauf captured in his quest for immortality, but none of that is made explicit here—all you know is that Tad is concerned about "the others" that he "left behind." The meaning is clear enough to those who know the story already, but newcomers won't get a clear picture of the children's plight or the extent of Stauf's misdeeds and motivations. Muddying the waters further are Stauf's frequent lies to Dr. Richmond about his own history that aren't clearly marked as such to observers, so that players without previous knowledge of where he came from might perceive the contradictions across storylines as inconsistencies or plot holes.

One of the most memorable aspects of The 7th Guest was its soundtrack by George "The Fat Man" Sanger, which simultaneously brought the game to vivid life and lent it an incomparable air of foreboding. My most pressing question going into The 13th Doll—even more so than how the puzzles or story would turn out—was how Attic Door would follow such an iconic score. Sanger's own compositions for The 11th Hour paled in comparison to his work on the first game, so it seemed unlikely that an amateur developer could do better than the man himself. What a pleasant surprise, then, to find that composer Chris Bormend has actually managed the seemingly impossible and created an original soundtrack that's every bit as lively, dynamic and compelling as Sanger's original. The 7th Guest is a clear inspiration, but aside from an opening homage to that game's classic title track, Bormend's work never tries to imitate or play off of its forebear. The result is a score that feels of a piece with its predecessor while still maintaining its own distinct identity.

Where the game unfortunately stumbles is in presenting its story. Frequent cutscenes serve up great helpings of exposition, both in the form of dialogue between characters and instructions from your spectral guide, but they come so often that it's sometimes hard to keep track of what's going on and why. One of Richmond's coworkers is introduced early on and seemingly set up as a potential love interest, overshadowing the much more important backstory she delivers about Tad, Stauf and the house in the process, but aside from one or two mentions later on she's absent from the rest of the game. Numerous hallucinatory visions pop up for both player characters that tease details about their pasts, but so little is made of these that it's easy to forget who hallucinated what. Similarly, Stauf and the Woman in White provide conflicting versions of their plans, motivations and connections to each other, but since you can only get half the story at a time, you're liable to forget the fine details between revelations.

Despite all the numerous plot threads in play, many elements of the story wind up feeling underdeveloped. What makes the titular doll so important? Why does Tad immediately trust the Woman in White, who (as far as we know) he has never met before she came to him in the asylum? If Stauf could start building his machine—not present in the first game—despite being dead for a decade, why does he need Richmond's help to complete it? And why is Dr. Richmond, a rational man who goes to great lengths to disabuse Tad of a belief in the supernatural, so quick to abandon his role as Tad's caregiver when a dead man's disembodied voice promises to grant him a wish? The game never addresses any of these questions, instead seeming to treat the answers as self-evident, but if they are I personally never figured them out.

You might expect a game with so many drawn-out cinematics throughout its runtime to take its time crossing the finish line as well, but surprisingly each of its five possible endings—two for Richmond, three for Tad—is shockingly brief. Which ending you get is determined by the choices you make at a few set points in each character's story, but as none of the climactic cutscenes lasts more than 30 seconds, there's little sense of weight to your choices, especially since (apart from a difference in point of view) two of the endings are basically identical.

At most points the solid production values make it easy to forget that The 13th Doll is a fan-powered production, but the acting on display for most of the characters serves as a frequent unfortunate reminder. FMV games aren't usually known for their top-shelf acting, but with the exception of the returning Robert Hirschboeck, who's pitch-perfect in his third outing as Stauf and who seems to be having the time of his life, the cast of The 13th Doll simply don't come across as experienced performers. Both of the leads often neglect to enunciate their lines so that dialogue is delivered in a breathless rush, and actors playing roles from the 1930s and earlier speak with the diction and cadence of modern twentysomethings. In much of her delivery, the Woman in White sounds just plain bored. Combined with the already difficult-to-parse story, it becomes hard to invest emotionally in what's going on.

It's significant that the phrase "A Fan Game of The 7th Guest" is displayed so prominently on the game's title screen. This immediately communicates the type of audience The 13th Doll is trying to appeal to, while also serving as an up-front disclaimer that some elements of the production tend toward the amateur side of things. Even so, it would be wrong to dismiss this as "just" a fan game: the puzzles are as good as anything you'll find in an A-list title, and much of the experience is skillfully designed and memorably executed.

What's most impressive about The 13th Doll, though, might just be that it exists at all. Ambitious fan sequel announcements were a dime a dozen in the early '00s, with most vanishing quietly back into the aether before long; that Attic Door not only stuck with theirs over the course of 15 years but successfully brought it to life as a full, commercially-viable release is a remarkable achievement. While it doesn't quite rise to the level of the classic horror puzzler that inspired it, The 13th Doll is a fairly enjoyable tribute that ought to please those who spent the past two decades wanting more Stauf. Even the most demanding will have to admit it's better than The 11th Hour.

(This review is brought to you in part by the patience of my mother, who solved The 7th Guest's "slyly, spryly, tryst" puzzle for me when I was eleven. Love you, Mama!)